The Rabbit Hole of Paul

Paul Taylor Dance Company artistic director Michael Novak on reconstructing dances and the blindfolded Rubik’s Cube challenge of programming a season

For many dance companies, programming shows is relatively simple—they’re performing a single evening-length work, or they have a small repertory that doesn’t require a lot of decision making. For Paul Taylor Dance Company artistic director Michael Novak, programming is a part-time job. Novak has a catalog of 147 original Taylor works to consider for the company’s annual touring engagements—PTDC performs at more than two dozen venues worldwide, each with its own stage dimensions, technical specs, and audience profile—and its fall home season at Lincoln Center in New York City. Programming is an ongoing puzzle that Novak solves with sensitivity and savvy.

To be sure, not all 147 of Taylor’s works are stage-ready; many early pieces have not been seen since their origins in the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s. So Novak has assumed another kind of stewardship, that of reconstructing select dances from the Taylor archive. It takes a village to raise a dance from dormancy, and Novak’s team includes rehearsal directors Bettie de Jong and Cathy McCann, original cast members, and current dancers, who work from personal recollections (when memory serves), Taylor’s notes (when legible), and video (when available) to restore long-lost works and reveal glimpses Taylor’s evolution as an artist.

The results will be on view during PTDC’s summer season at the Joyce Theater, running June 17–22. Along with the perennial favorites Cloven Kingdom (1976), Polaris (1976), and Esplanade (1975), Novak’s program includes the premieres of two reconstructions: the abstract duet Tablet (1960), with design created by the minimalist artist Ellsworth Kelly and re-created by Tony Award–winning set and costume designer Santo Loquasto, and Churchyard (1969), a study on the sacred and the profane set to a medieval-influenced score by the photographer, conceptual artist, and composer Cosmos Savage.

Novak specifically chose the Joyce for the new debuts of Tablet and Churchyard, and he explains why in our Zoom interview. He also sheds light on the unique complexities of programming PTDC, the (mis)adventures of reconstruction, and how sometimes the very old can feel very new. Our conversation is lightly edited.

Claudia Bauer: When you’re managing the oeuvre of an artist as prolific as Paul Taylor, how do you select pieces for a program?

Michael Novak: There’s a lot of factors that go into programming. On the macro scale, I look at the touring history of every venue we’re going to—probably twelve to twenty-eight venues in a year—and then I look for dances that we’ve never done in that venue, ideally in the last twenty years. And then I start stitching together what those dances are, also relative to what’s going to be at Lincoln Center, so I can start getting those dances on the stage.

One of the big factors I’m homing in on is the venue itself—how large is it, what are the dimensions like, is the audience close or far away? And this is where the Joyce comes into play for me. When I first became artistic director and I was looking at Paul’s works that he made midcareer and later, it was a larger company, larger ensembles, a different use of space than what you see in the 1950s and 1960s. Not just Paul’s work, but a lot of early modern dance, was built for small stages and small spaces. Some dances can hold their own at Lincoln Center, but it’s a different viewing experience. So the Joyce can be kind of a foil to Lincoln Center for me—something more intimate, where the audience sits much closer. It’s also a very educated dance audience. So if I want to go down the rabbit hole of Paul, the Joyce seems like a great venue to do it.

CB: That is fascinating—I had no idea there was an eight-dimensional-chess aspect to programming.

MN: Programming is probably one of the most complex puzzles of the job. And when we get to Lincoln Center, the other major factor to consider is the orchestra, and the musical variety, and what it means for certain instruments on certain nights. I could have my whole [Lincoln Center] program together, and Orchestra of St. Luke’s looks at it from an instrumentation standpoint—this piece has forty musicians, this piece has two; this one needs two pianos, but we don’t have space. [The company performs to recorded music at most other venues.]

CB: From the audience perspective, the magic just happens. We have no idea of the deliberate puppeteering behind the scenes—I’m never going to see a show the same way again! There are also many different moods in the works you present on a bill. What mix do you try to create?

MN: The program needs to have variety from a design standpoint and from a musical standpoint. Also, showing Paul’s range as a choreographer. Most audiences at the Joyce know Paul and know modern dance, so there’s the exploration of, how did he become Paul? We know Cloven Kingdom, we know Esplanade. But what happened between 1954 and 1976? These early works are odd and beautiful and curious and crafted really, really well. You can tell there’s a genius mind at play that’s working through things.

The early works give more context of where his movement style came from, before his style was codified. One of the things we’re running into in Tablet and Churchyard is that this is all pre-Esplanade. My theory is that once Paul stopped dancing and was watching his dances, and creating them from the front, that’s when his style begins to get codified. Shapes become clearer and more refined. Before then, he was in the dance, so you’ll see a wildness, you’ll see people all have the same intention but it’s being manifested differently. The precision we see in a Promethean Fire is not there in the 1950s and 1960s. So, do we choose to keep that wildness? Do we choose to clarify it a little bit? It’s a constant debate in the studio: “It needs to be messy” versus “This looks too messy.” [laughs]

CB: I’d be curious to see things danced as they were. You’re debating between that and a William Forsythe–style adaptation to the dancers we have in front of us.

MN: I think of a reconstruction as trying to be as close to the original as possible, and a reimagining as a springboard to add your own flavor. This is very much a reconstruction. Choices that I’ve had to make have been in consultation with original cast members as well. We have one video [of Churchyard]—that’s it—from 1974, and it’s very hard to see what’s happening. So there’s inferring that needs to happen. But we’re trying to keep it within the realm of, he hadn’t made these other [later] things yet, so we can’t make it too clean.

There was a weird moment when [Churchyard] original cast member Nicholas Gunn was with us for a week. It was the first dance he ever made with Paul, so it’s very much in his DNA. There was a moment in the video where there is this couple dancing, and there is this lift—Nick and I, two different generations, at the same time we both went, He wouldn’t have done that. That’s not Paul. So then the question is, what is it, and what do we do? Also, dancers are different now—their bodies are different now, cross-training is different now. There’s a men’s section in Churchyard that’s very, very hard. Nick Gunn said it was the hardest thing he ever did, it was the hardest thing in the repertory—and then he did Cloven Kingdom, and that was the hardest thing. But Nick was never in Mercuric Tidings, he was never in Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal). These [current] dancers have done the full extent of the repertory, and they’re like, “We’re tired but we’re okay.” It’s a different generation, taking on a work from a different generation.

CB: It must be fascinating for dancers who didn’t know Paul to get inside of his mind through moving differently.

MN: They love digging into it. It’s been a lot of homework, a lot of teaching. They love Paul’s notes, when we can read them, and with Churchyard, we can’t really. A couple things are clear, but a lot of the notes are in pencil on notebook paper, and by now that lead is almost gone.

CB: Is there an element to reconstructing that’s kind of like caulking tile? Like “this is in the spirit of…”?

MN: A hundred percent. Think of Jurassic Park—they have the dinosaur DNA, and they fill it with frog DNA. We have these gaps in the sequence code, and we’re like, is it a chassé? is it a skip? is it coupé? We’ll try different things and fill it in.

CB: Are you planning to accelerate reconstructions while you have original cast members to work with?

MN: First of all, oral histories are essential to our art form—alumni histories and perspectives. That’s another reason why these reconstructions are important, because we’re starting to lose that first generation. What’s interesting is that alumni memory of works is sometimes different. I have the original cast of Churchyard—some people don’t remember anything about it; they performed it once or twice, and then they were done. Other dancers have it more ingrained in their body—and then they watch it, and they remember where it should live in the body. It happens viscerally.

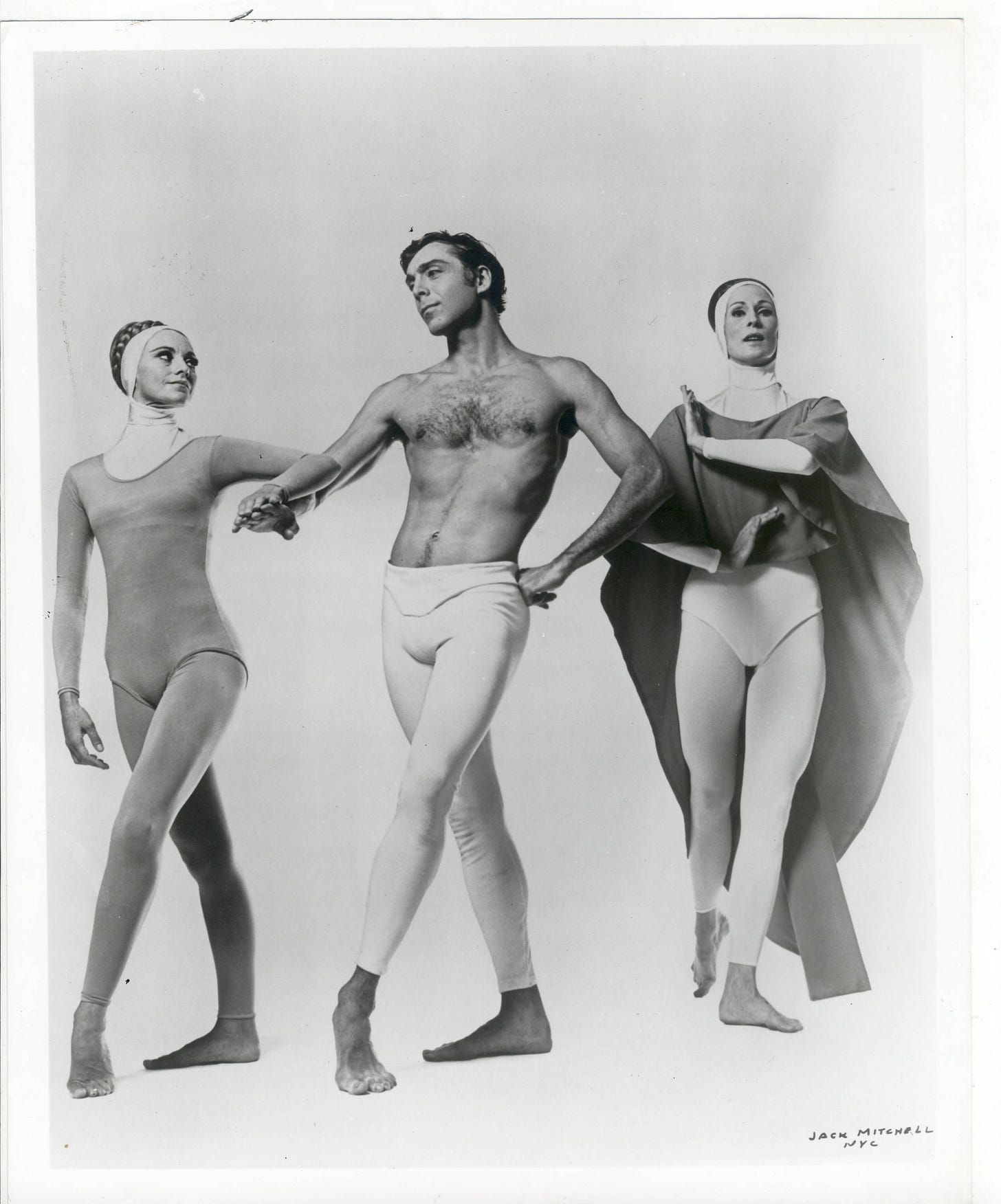

There’s a host of works on my list that I’m starting to work my way through, that are quite beautiful, curious, unusual. Tablet is gorgeous. I’d heard rumors about Tablet. Most people don’t know that Pina Bausch was in the company for a little bit [1960–1962], and Paul made Tablet on Pina and Dan Wagoner. We have a video of Pina; her angularity and her frame are so unique. It’s fascinating to see her in the context of Paul. And then there’s Ellsworth Kelly doing designs, playing with flat, bold color. There’s a whimsy to it that’s very different in the repertory. And the music [by David Hollister] is great. And like Churchyard, it’s just been sitting in the vault.

CB: Is there a subset of Paul’s work that you can’t reconstruct because there’s not enough information?

MN: There’s probably 10 or 15.

CB: That’s it?

MN: Paul took really copious notes—then again, it goes back to whether we are reconstructing or reimagining. A good example is that Tablet was originally designed with this backdrop by Ellsworth Kelly, and as performances continued, they stopped using the drop. I can’t remember if they lost it, or if Paul didn’t like it, or if Ellsworth didn’t like it. I love the drop; I wanted to re-create the drop. What we ended up finding was an interview with Ellsworth where he talks about how he didn’t like how the drop was made, and why. So now Santo Loquasto has the original designs, he knows all of the things that Ellsworth wanted to be better about it, and he is fixing those things for when we bring it to the Joyce. These voices from the past are giving us clues about how to make the work come back and feel more vibrant than when it premiered.

CB: It’s so magical when these historical pieces come together.

MN: Oh, when those moments come together, it’s great. With Tablet, when the video was transferred from the 16mm, they flipped it. So we were putting it together, and we got Paul’s notebooks out, and what Paul’s notes say—enter stage right, on the right foot—is not what’s happening in the video. So, we had to re-flip the video. It’s all these little things that give you clues. It is magical when they pop up.

CB: It’s as close as we can come to getting into a time machine and seeing Paul’s mind at work. And seeing the reconstructions in the context of what he did later, like Esplanade, could be very revealing.

MN: I’m thinking a lot right now about the year that something was made, and the significance of that or the hindrance of knowing that. There’s a dance of Paul’s called Scudorama, from 1963. We were at a conference for presenters around the world, and there was a TV that shows excerpts of performances, like a slideshow. This particular presenter only wanted contemporary, they didn’t want any classic Taylor. A video of Scudorama came on, and they were, like, “We want something like that,” thinking it was a new work by a contemporary choreographer. It’s a great check, because you’re like, what’s contemporary and avant-garde is relative. Are you attached to a date? Or are you attached to what a piece is doing, and how it’s pushing something forward? I love swimming in that water. If we don’t put a date on it, what year do you think that was made? What if I told you it was a world premiere? Would you write about it differently? It does affect the audience’s viewpoint.

CB: It affects the critics’ viewpoints as well. If you were to present a work without the usual identifiers and challenge them to guess, I bet a lot wouldn’t be able to tell.

MN: Yeah. I remember watching a video of [the Ballets Russes’ 1917] Parade, that the Joffrey Ballet reconstructed, with the sets by Pablo Picasso. I was like, if this premiered today—it’s still ahead of its time. Even when we brought [Kurt Jooss’s 1932 antiwar ballet] The Green Table here. It’s approaching 100 years old. A few elements might be a little bit dated, but it’s timeless. It gets you every time. I love that.

CB: We rely on those indicators to help us interpret things.

MN: Oh, a hundred percent.

CB: But there’s something so refreshing about challenging yourself to look at something without all those bumper rails and asking how do I feel about it, right now?

MN: In the digital age that we’re in, it’s interesting for audiences to have to sit in the theater and not know.

CB: There’s no ChatGPT in the theater.

MN: Nope, and for the next 22 minutes, you might not know what something means. You’re going to have to go on a journey. I try to lean into that when I program. If we’re touring to venues that don’t see a lot of dance or never seen the company before, I give them permission to not know, to talk to the person next to them at intermission. It’s okay, you’re not missing out. There are things that we don’t know while we do it.

CB: On a different topic, the opening night of the 2024 Lincoln Center fall season was on Election Day, and in your curtain talk you were deeply concerned about the future. What does the landscape look like to you now?

MN: If you trace it back to coming out of the Cold War, all of us—Limón, Ailey, City Ballet, ABT, Graham—we were out touring the world because of the State Department. We were ambassadors for freedom of expression. The election for me was an important warning, because I woke up and I realized I had one job to do—to get the sixteen dancers to do their job, which is to bring art to the world. And anything that gets in the way of that, is in the way of it. I’ve been off social media since—cold turkey. They’re the ones on the stage, connecting with audiences and teaching the next generation. It almost shifted me into hyperfocus on them and their responsibility as artists in this moment in time.

It’s hard. It’s scary. And this is exactly the time that we have to buckle our seatbelts and get angry and do work, and create more, and bring back pieces from the past. And don’t stop—expand. Don’t shrink or retreat—move forward. Even if we don’t necessarily know what that means, or where the funding is coming from, it doesn’t mean we sit in the back of the room and wait. We can’t. Onward.

CB: For us as human beings, and for the health of our society, we need art.

MB: And audiences need it. All audiences need it. Everywhere we go. Dance brings something so essential and unique to the world because it communicates without words. The closest thing I can compare it to is sports. There are moments in games where everyone is inhaling and exhaling together, that communal experience of how the body is responding in that moment in time. But dance does it like nothing else can.

Paul Taylor Dance Company performs at the Joyce Theater June 17–22, 2025. Tickets are available here.