January 2025 was already going to be an epic month for the choreographer and dance historian Jody Sperling. On the 27th, her New York City–based company, Time Lapse Dance, was scheduled to embark on a two-week, six-performance tour of Egypt, presented by the Hakawy International Arts Festival and realized through three years of negotiating, planning, fundraising, and rehearsing.

Sperling is as much a humanist and ethicist as she is a dance maker, and she uses her art to highlight ecology and climate change in works like 2016’s Ice Cycle, created during a residency with an Arctic science expedition, and 2022’s Plastic Harvest, which turns pollution into a visual spectacle of dancers costumed in billowing plastic shopping bags. Her intentions for the tour were manifold: In addition to bringing people together across cultures and generations while inspiring environmental awareness, it would pay homage to the 1905 Egyptian tour of Loïe Fuller, whose iconic serpentine dances thrilled international audiences then and inspire Sperling’s contemporary choreography today.

But not even Sperling’s vivid imagination could have conjured what actually took place. On January 26th, the literal eve of departure, she received word that the U.S. embassy in Cairo was rescinding the $30,000 grant it had awarded for covering tour costs. The tour would be one of countless casualties of the new administration’s funding freeze.

Over Zoom in early March, Sperling talked about why she took a gamble and took the company to Egypt anyway, why it was worth it and what helps her stay hopeful. “I feel very lucky, because I think what makes us whole as humans is to have meaning in our life, and the current moment is making our actions very meaningful,” she says. “There’s no silver lining in what’s happening right now, but I feel a sense of purpose.”

On March 21, Jody Sperling/Time Lapse Dance will perform Memories of Egypt at the New York Society for Ethical Culture, where Sperling has been the Ecological Artist-in-Residence since 2022. The program includes the world premiere of Fractal Memories as well as Arbor, Serpentine Swells and Sperling’s solo Piece for Northern Sky. Tickets are free—RSVP here.

The following is an edited excerpt of our conversation.

Claudia Bauer: So…the trip did not go quite as planned.

Jody Sperling: We’d been planning this tour for three years. It took a long time to line up the funding—TLD got a grant from Mid-Atlantic Arts, and the festival got funding for production costs, hotel and everything from the U.S. embassy in Cairo. We had multiple back-and-forths on every aspect of the tour—the logistics, the schedule, the lodging. We had to reschedule because there was a public health crisis in one of the tour cities. We were scheduled to depart on January 27th. On January 26th, I received a phone call—this is at eight on a Sunday morning—from a 202 [the Washington D.C. area code] number. I listened to the message, and it was someone from Cairo saying to call her back right away. I got her on the phone, and she was like, “I have bad news. The grant is terminated, and you must cancel your plans immediately.” I was in shock.

The U.S. embassy was putting up $30,000 for the tour. And if we didn’t go, we would have had to refund [another grant we received]. Our plane tickets had been purchased, I had contracted with the dancers, they had taken time off their day jobs. It would have cost us more not to go than to go. The embassy had paid a $10,000 deposit, which we had sent to the festival before the end of the year. The second payment, of $17,000, was approved on January 8, and it was supposed to take 20 days to go through, so we were expecting it to hit the bank imminently. I had to wire $17,000 to Egypt and rewrite our contract. I rallied a lot of support from people who are really strong supporters of TLD. I reached out to the State Department, and they told me that the grant was terminated, not frozen, because it “no longer effectuates agency priorities.” But they didn’t prevent us from going.

I’m really glad that we went. It was an amazing experience. We did three performances in Cairo, one at the Bibliotheca in Alexandria—we got a tour of the library and did a workshop with the students—we went to Aswan, we did a photo shoot on the Nile, and we did two performances at an amphitheater outdoors. And then, the very last day, through a friend of a friend who had told me about a home for orphans called The Littlest Lamb, we checked out of the hotel at one in the morning and performed there and did a workshop for the children. That was probably the highlight of the whole tour. The woman who founded The Littlest Lamb is committed in such a deep way to meeting all their needs.

CB: You’re deeply personally motivated by what you do, and you had specific intentions for your two weeks in Egypt. I’m wondering how the turn of events might have influenced you—if you suddenly felt different emotions about the purpose of the tour.

JS: Politically, things were only just starting to happen when we were there. In terms of the tour itself, I feel like we accomplished what we set out to accomplish, and I feel very proud about that. I feel like we wanted to present a program that shared a joyful experience with multigenerational audiences, particularly youth, around experiencing a sense of one’s own body in nature.

And almost every performance included either a talkback or a participatory experience. In a workshop that we did, we started with having the audience close their eyes and imagine roots growing out of their feet, into the ground, and that all of the roots of all of the people in the audience were intertwining and connecting, and that was making everyone in the audience stronger and more stable. We opened our eyes and the wind would blow, and we all had this stability and strength because of these underground roots. That was a way to visualize the message that was embedded in the choreography, but also embedded in our process and what we’re trying to communicate to the greater public. We want to share and model these interconnected experiences.

CB: The audiences weren’t yet aware of the political situation, but you were. I imagine that I would feel defiant and righteous and angry.

JS: For the first week, I was on the phone trying to raise money. And because of the time difference, I wasn’t getting enough sleep. I was stressed out by the practicalities, and I also was buoyed by the amount of support I was getting. So, I did feel righteous, and I did feel kind of galvanized. And I felt the meaning of our work was coming to the surface. In America, we have this sense of complacency around the work we can make, and I think we’re in a period now where everybody is going to have a choice about the extent we’re gonna stay public with messaging that might run counter to, let’s say, executive orders. Are you going to be in compliance? Are you going to opt out of any kind of resistance?

CB: The reasons for your grant being terminated have not been specified, but I feel confident that your intentions for the tour came head-to-head with the very forces that you oppose in your work. Now that you’ve had some time to think about it all, does it affect your feelings about the show you have coming up at Ethical Culture?

JS: Yeah. I’m an artist who has been very allied with scientific inquiry. I went to Stuyvesant High School. I went to the Arctic with polar scientists. In thinking about, with Arbor, the tree ecology that informed it, and with Wind Rose, the atmospheric circulation data that informed it, I feel like the attack on science has been rising to the top of my outrage. NOAA and NIH and NSF, to me, have been pinnacles of American achievement. American scientific innovation is the foundation of all of the industry we have now. When I think about NOAA and all the data they have been accumulating—only because we have that data can we verifiably prove that humans are warming the planet. To dismantle that agency, to dismantle the science we need to be able to prevent and forestall the effects of climate change, drastically reduces our preparedness against disaster. I’m mad about my grant, on a personal level. But also, my friends from high school—they’re doctors, and their NIH grants are being cut, and they are trying to save lives!

In terms of the show, I feel like a lot of people are very despairing, and I feel like my role in this world right now is partly to be a bridge between despair and action. It’s overwhelming, the assault is on so many fronts. It creates an emotional situation in which it is very hard to act. We always look to create experiences of joy, of beauty, of transformation, that are visions of what could be. I think that has often been lacking in climate discourse—there’s a lot of apocalyptic thinking, and what we need is very positive visioning of how much better this world could be if…or how beautiful it would be if… And I can imagine it filled with trees that would cool the cities, and we can plant little forests, and we can all live in peace. They’re connected—this positive visioning for the world is part of what I think of our dances as being. With Arbor, we’re trying to get out of being stuck in being human—what would it feel like to be a tree, and how would it feel to be entwined on a root level? In the workshops, we talk about trees as teachers. They can liberate us; they can help us get out of this slump of being people.

I’m excited about Fractal Memories, which is one of the pieces in Obsessed with Light. [The 2023 documentary about Loïe Fuller features Time Lapse Dance.] The music and the dance are structured around fractals, which are an organizing principle of nature. I was obsessed with fractals in nature, but I was also thinking about it temporally, this way that larger movements in history occur on different scales. Little violence begets larger swells of violence. But it’s the same thing with love—love will create this feedback loop with swells of peace. In thinking about Loïe Fuller, because it’s a tribute to her, in the beginning of the piece there’s a video feedback loop where you see my image projected smaller and smaller and smaller. I was imagining going back to Loïe. Later in the piece, you see the dancers stacked up front to back—the idea that this chain of bodies becomes materialized.

In the finale, the piece is kind of like Fire Dance. [Loïe] created the original Fire Dance in 1896, at the dawn of the fossil-fuel age, and now we live with the effects of that. The performer self-immolates. I feel like doing this dance now means a lot. Especially having family in Los Angeles—it’s packed with meaning for me. I was hesitant, in a way, to end the program with Fire Dance, because I feel like my role in the world is creating this more hopeful thinking, in creative form.

CB: I can see why you would weigh the pluses and minuses ending the show with Fire Dance. But the world always feels immense, and in every generation, artists attempt to call attention to what is happening, so it feels of a piece that you are presenting hopeful things but ending with Fire Dance. I’ve been asking myself lately, As creative people, we try to help make the world a better place, but what can we really do? Having these experiences together is what we want and need, as people. There will be no peace if we can’t do that.

JS: I feel like being the Eco-Artist in Residence at Ethical Culture has helped me define a role as an artmaker, which is that I am advocating for ethics in the production of artmaking, not just the content of it. Having this home in the city has cultivated that thinking in me: What does it mean to be an ethical human, and what does it mean to be an ethical choreographer? That thinking was also a big part of making that decision on January 26th. I mean, if I weren’t an ethical person, I could have not paid the dancers, or the company could have reneged on the contracts.

The fundamental truism of all religious, spirituality, ethics principles, philosophies, is that we’re all connected. And it’s not a fantasy—we are materially connected. Yes, there are these horrible things that keep happening in the world, but there are also incredible numbers of really well-meaning, deeply engaged people who have also been able to instigate good. That work is often invisible, because what we see is the destruction, and it’s louder and more powerful. I’m very sobered, but I do think that there will be phoenix-like rising of good, collective actions in the future.

CB: Loïe and her dancers toured Egypt in 1905. As you reflect back on your tour and look forward to the show coming up—this is almost a spiritual question—what does it feel like to span time in that way?

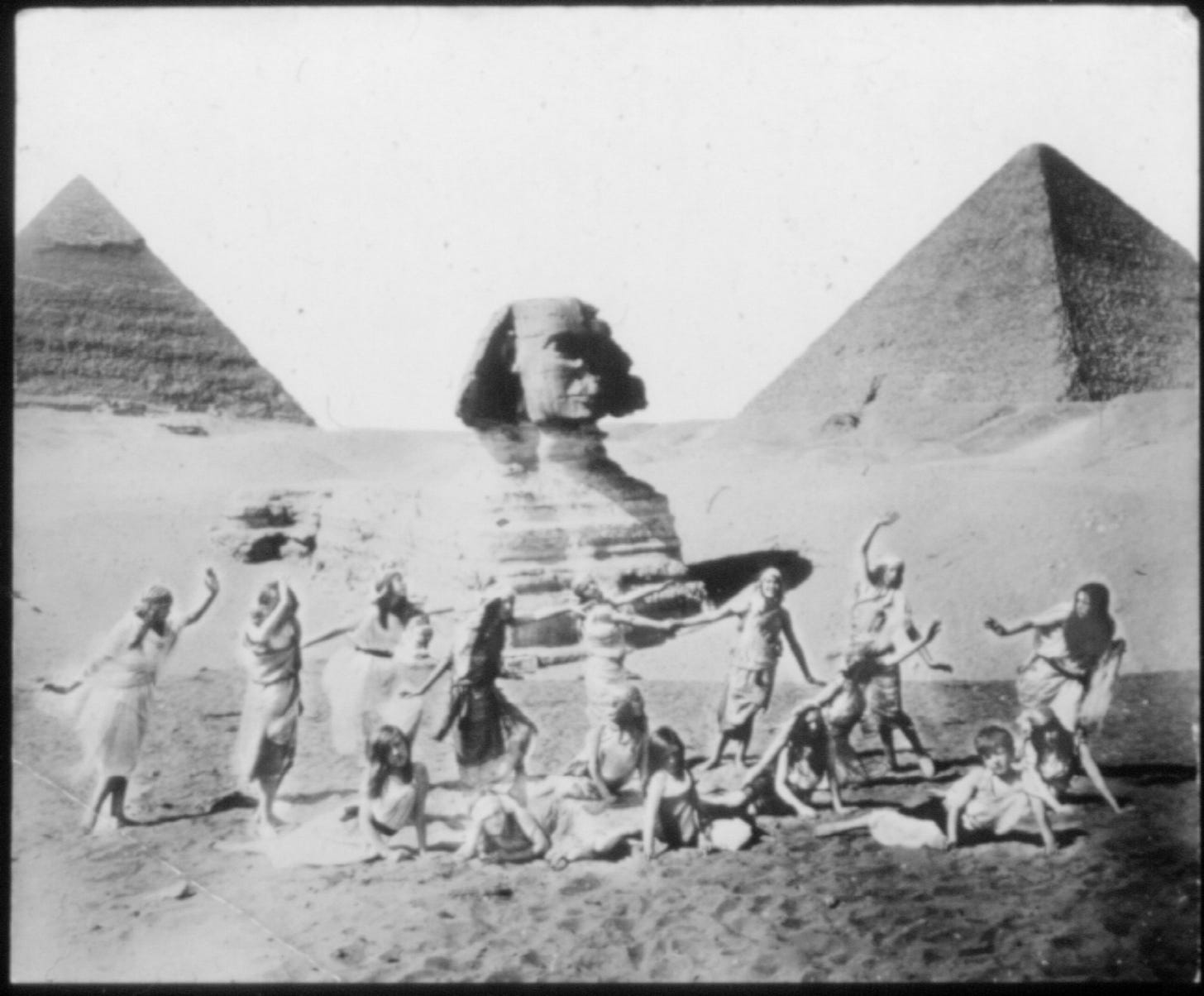

JS: One of the reasons that it felt so right for us to go to Egypt was this idea of following in Loïe’s trail, and those iconic photographs of her in front of the Sphinx. Immediately when we booked the tour, I said, We have to go there. Where they were has been excavated over the last 120 years, so we were in a slightly different place, but you could see the same pyramids. It felt really meaningful. Loïe performed in New York City, but those theaters are gone. I had the same feeling when I went to the Folies Bergère—a kind of pilgrimage, I guess.

The company is Time Lapse Dance—we mess with time, it’s what we do. The illusory nature of time, and time being flexible and surprising and malleable, is a really great place to begin choreography. It’s a constant source of inspiration for me, thinking about the historical touchpoints and how they spiral through history and evolve. If you can catch those currents, it makes choreographing and creating art more like channeling than like building. That’s a really amazing place to be, when there’s a greater force shaping what you’re doing as you’re doing it, because you’re part of a bigger pattern that’s unfolding.

Learn more about Jody Sperling/Time Lapse Dance and RSVP for free tickets to the March 21 performance at the New York Society for Ethical Culture.